Email spoofing is like a fake return address on an envelope. The message can look like it came from your CEO, your bank, or your own domain, while the real sender is somewhere else.

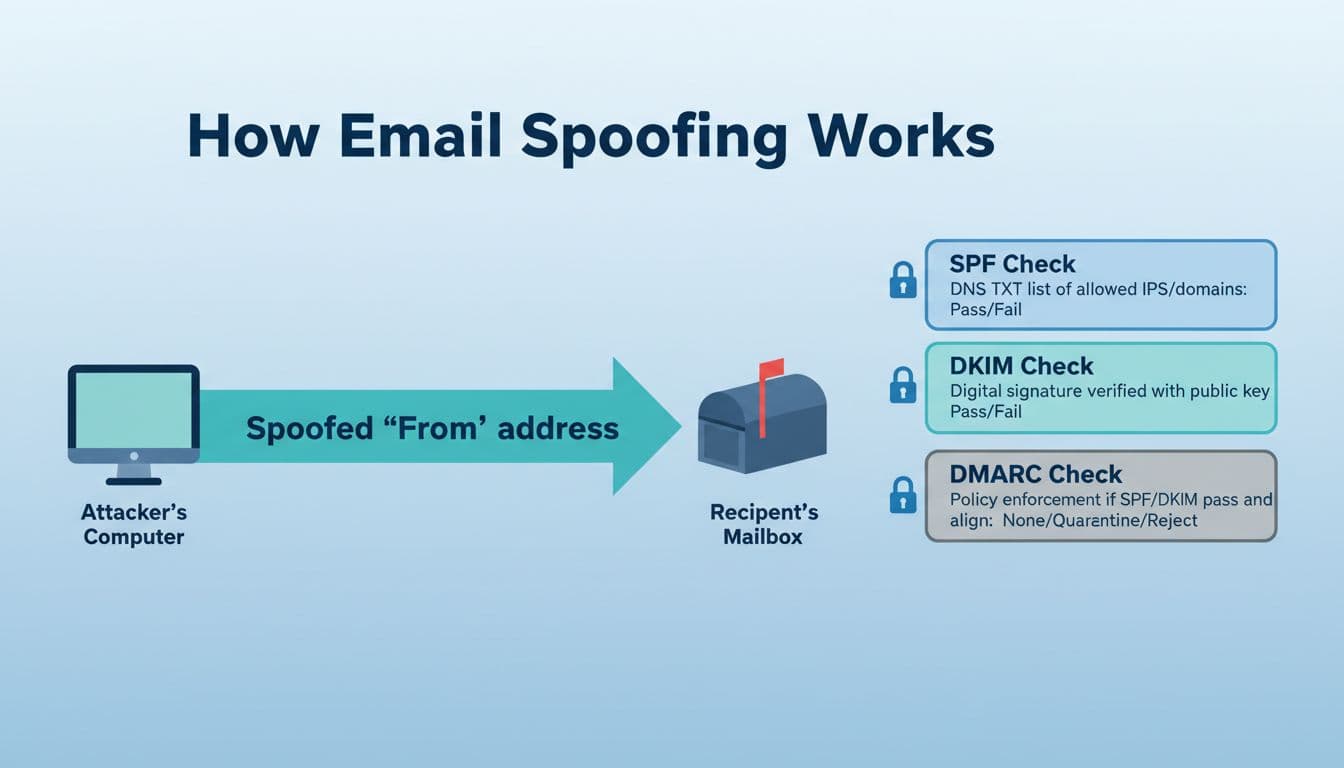

A practical email spoofing check has two parts. First, confirm what you’re seeing in the inbox (display name tricks are common). Second, read the hidden header results that mailbox providers use to judge trust: SPF, DKIM, and DMARC.

By the end, you’ll know how to spot spoofing in Gmail and Outlook, then publish SPF, DKIM, and DMARC safely, without breaking your legitimate mail.

How to do an email spoofing check in Gmail and Outlook (in the inbox)

Before you open headers, do a quick reality check. Attackers often rely on your eyes glossing over details.

Gmail (web and mobile, menus can vary)

- Open the message.

- Click the three dots (More) near the reply button.

- Choose Show original (web) or View details (some mobile clients).

- Look for “From”, “Reply-to”, and any warning banners.

Also click the sender name at the top of the email. Gmail usually reveals the full address and the “mailed-by” or “signed-by” hints. If the display name says “Accounts Payable” but the address is a strange domain, treat it as suspicious.

For more general red flags to look for (especially when the message feels urgent or odd), CMU’s guidance on identifying spoofed phishing emails is a solid checklist.

Outlook (new Outlook and Outlook on the web)

- Open the message.

- Select the message actions menu (three dots).

- Choose View or View message details (wording varies by version).

- Find the Internet headers or Message source section.

In Outlook, also expand the From line if it’s collapsed. A common trick is a lookalike display name paired with an external sender address.

If the email claims to be from your own domain (example.com), but it came from an outside mail system, headers will usually expose it.

Reading headers: what “SPF=pass”, “DKIM=pass”, and “DMARC=pass” actually mean

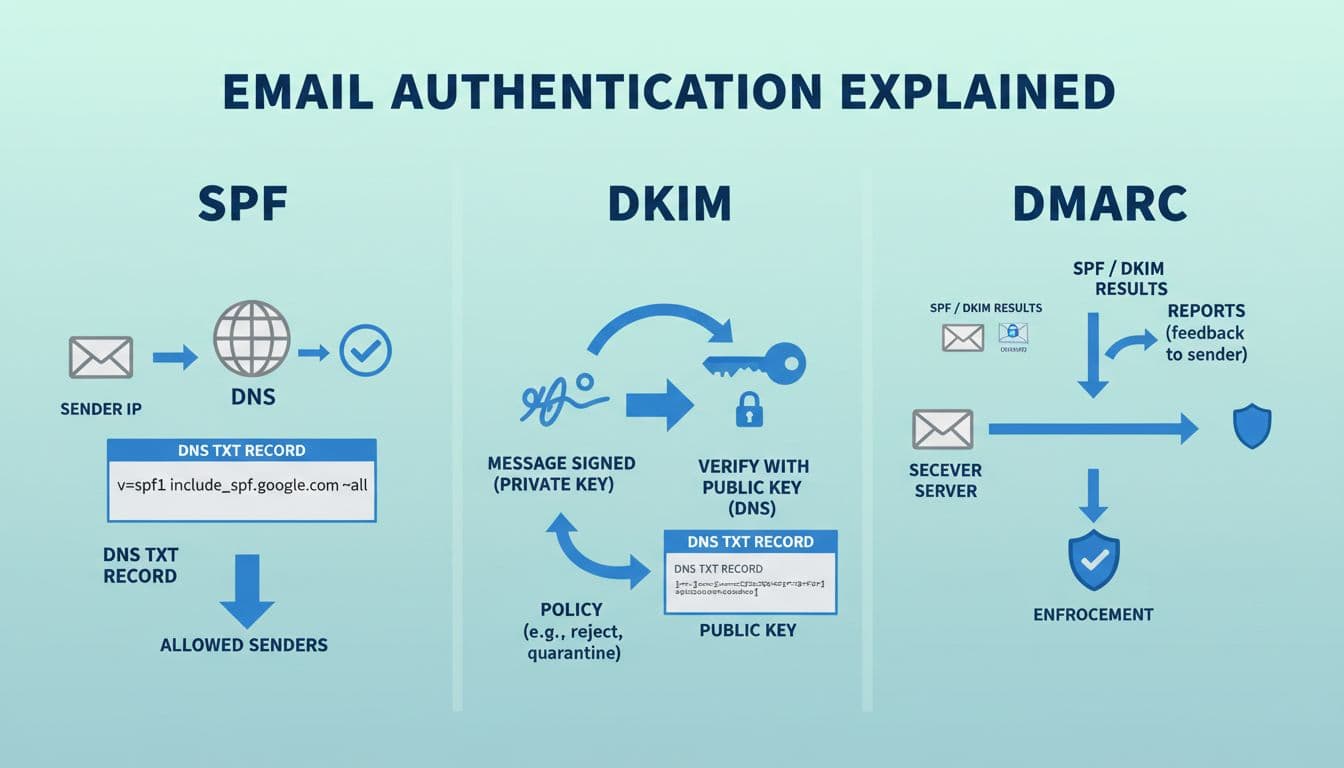

Think of SPF, DKIM, and DMARC like three locks on the same door. Any single lock helps, but DMARC is the bouncer that decides what happens when something doesn’t check out.

The simplest place to look is the Authentication-Results header. Here’s a safe example snippet and how to read it:

Authentication-Results: mx.google.com; spf=pass smtp.mailfrom=mail.example.com; dkim=pass header.d=example.com header.s=selector1; dmarc=pass header.from=example.com

What it means:

- spf=pass: The sending server’s IP matched the domain’s SPF rule for the envelope sender (

smtp.mailfrom=). - dkim=pass: The message had a valid DKIM signature, and it matched the public key in DNS (

header.d=is the signing domain). - dmarc=pass: DMARC accepted the message because SPF or DKIM passed and aligned with the visible From domain (

header.from=).

The part most people miss: alignment

DMARC isn’t satisfied by “SPF passed somewhere” or “DKIM passed for a vendor domain.” It wants the authenticated domain to match the From: domain your users see.

- SPF alignment compares the From domain to the

smtp.mailfromdomain. - DKIM alignment compares the From domain to the DKIM

d=signing domain.

Alignment can be “relaxed” (subdomains count as aligned) or “strict” (must match exactly). If you want more practice decoding real header fields, this guide on how to read email headers is a helpful walkthrough, and Valimail’s explanation of email authentication header results adds extra context.

SPF, DKIM, and DMARC setup: copy, paste, then roll out DMARC safely

In January 2026, the practical reality is simple: mail that can’t authenticate is more likely to get filtered, rate-limited, or rejected, especially at large providers. Set this up carefully, and test in a staging domain or subdomain if you can (example: mail.example.com). Coordinate with any email vendor that sends “as your domain” (billing systems, CRMs, newsletter tools, ticketing systems).

Step 1: Publish a single SPF TXT record (and keep it under limits)

Copy/paste example for example.com:

SPF TXT (root domain): v=spf1 include:_spf.google.com include:spf.protection.outlook.com ~all

How to read it:

v=spf1= SPF version.include:= approves senders listed in another domain’s SPF.~all= soft-fail for anything else (good while stabilizing). Later you might move to-all.

Pitfall: multiple SPF records break SPF. You must have only one. Another pitfall is the 10-DNS-lookup limit; if you hit “permerror,” you may need to reduce includes or flatten. AutoSPF’s write-up on implementing SPF records correctly explains the limit in plain terms.

Step 2: Enable DKIM signing (DNS ends up with a public key)

DKIM is usually turned on in your email platform admin, then you publish what it gives you in DNS (TXT or sometimes CNAME). Here’s a generic TXT example:

DKIM TXT (selector): selector1._domainkey.example.com TXT v=DKIM1; k=rsa; p=MIIBIjANBgkqhkiG9w0BAQEFAAOCAQ8A...

What matters:

- Your outbound mail is actually being signed.

- The

d=domain in headers aligns withexample.com(or a subdomain you control and plan for).

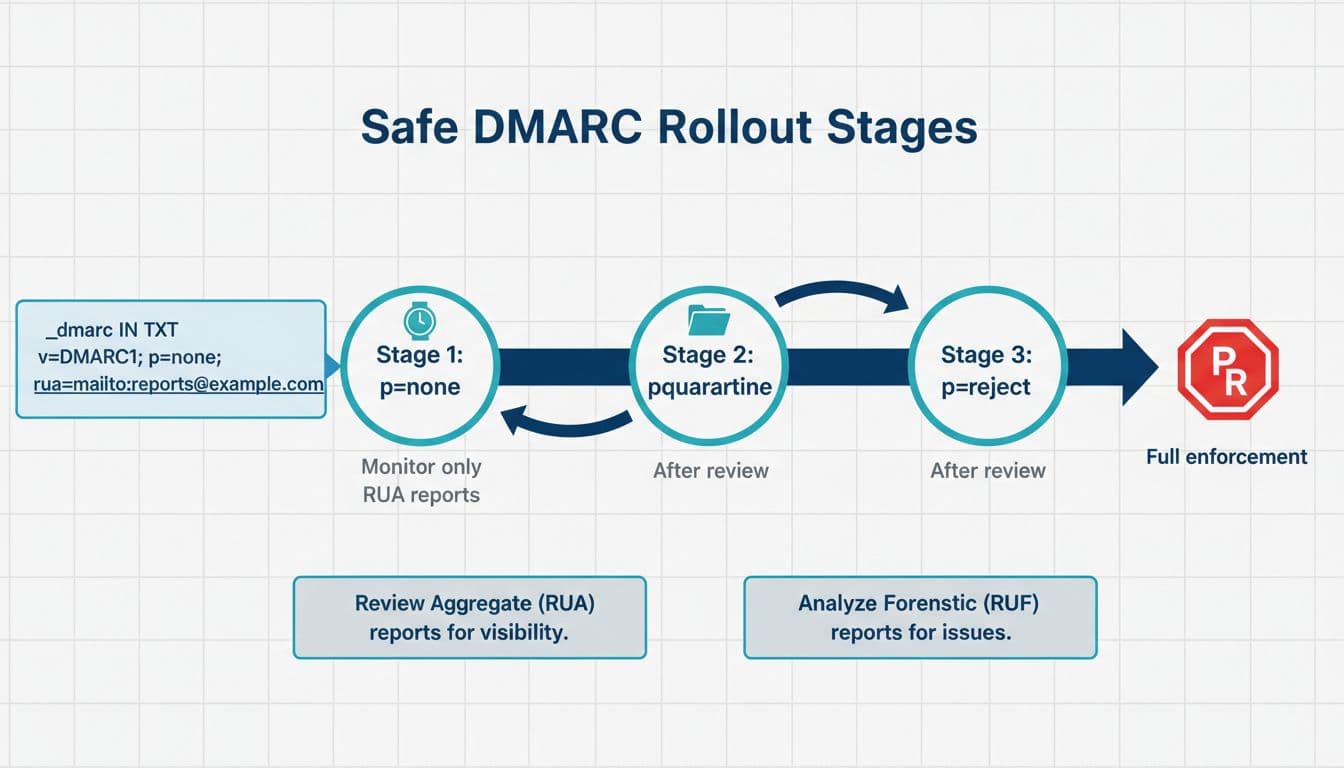

Step 3: Add DMARC, start in monitor mode, then tighten

Start with a monitoring policy:

DMARC TXT: _dmarc.example.com TXT v=DMARC1; p=none; rua=mailto:dmarc-reports@example.com; ruf=mailto:dmarc-forensics@example.com; adkim=r; aspf=r; pct=100; fo=1

DMARC tag meanings (plain English):

| Tag | Meaning |

|---|---|

v | Protocol version (DMARC1) |

p | Policy for failures (none, quarantine, reject) |

rua | Aggregate report mailbox (daily summaries) |

ruf | Forensic report mailbox (message-level samples, not always sent) |

adkim | DKIM alignment (r relaxed, s strict) |

aspf | SPF alignment (r relaxed, s strict) |

pct | Percent of mail to apply policy to |

fo | When to generate failure reports (varies by receiver support) |

Safe staged rollout:

- p=none for 1 to 2 weeks, review

ruareports, fix missing third-party senders, and confirm DKIM signs consistently. - Move to p=quarantine (often with

pct=25, then 50, then 100) once you see consistent alignment. - Move to p=reject when you’re confident, and keep monitoring.

Common gotchas to fix early: forwarding and mailing lists can break SPF, third-party tools may send without DKIM alignment, and subdomains might need their own plan (consider DMARC sp= for subdomain policy). DMARC reduces spoofing, but it doesn’t stop lookalike domains (example-co.com) from trying to fool people.

Conclusion

A good email spoofing check is repeatable: confirm the real sender in Gmail or Outlook, then verify SPF, DKIM, and DMARC results in headers. After that, publish SPF and DKIM, then roll out DMARC slowly so you don’t block your own systems. Once your reports look clean, tightening DMARC is one of the most practical steps you can take to reduce direct domain spoofing.